Foundations

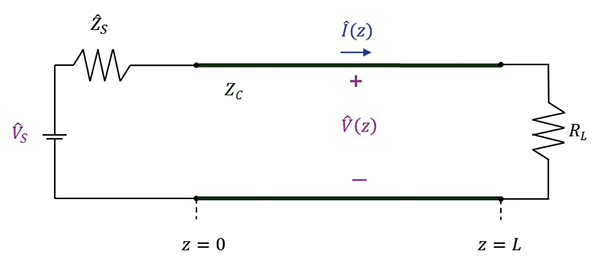

Consider the transmission line circuit shown in Figure 1. A sinusoidal voltage source ![]() with its source impedance

with its source impedance ![]() drives a lossless transmission line with characteristic impedance ZC, terminated in a resistive load RL.

drives a lossless transmission line with characteristic impedance ZC, terminated in a resistive load RL.

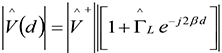

The magnitudes of the voltage and current along the line at any distance z away from the source are [1]:

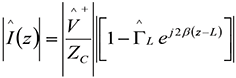

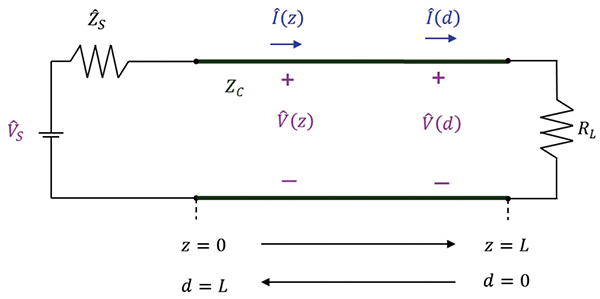

(1a)

(1a)

(1b)

(1b)

where |![]() | denotes the amplitude of the sinusoidal voltage wave, β is the phase constant of the wave and the load reflection coefficient is given by

| denotes the amplitude of the sinusoidal voltage wave, β is the phase constant of the wave and the load reflection coefficient is given by

(2)

(2)

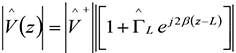

In the circuit shown in Figure 1, we have ![]() = RL. Now, consider the same transmission line but with the distance measured from the load to the source, as shown in Figure 2.

= RL. Now, consider the same transmission line but with the distance measured from the load to the source, as shown in Figure 2.

The two distance variables are related by

![]() (3a)

(3a)

![]() (3b)

(3b)

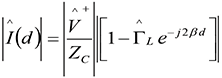

In terms of the distance d away from the load, the magnitudes of the voltage and current can be expressed as

(4a)

(4a)

(4b)

(4b)

There are four important cases of special interest that we will investigate:

The load is a short circuit ![]() = RL = 0

= RL = 0

The load is an open circuit ![]() = RL = ∞

= RL = ∞

The load is matched to the transmission line ![]() = RL = ZC

= RL = ZC

Arbitrary resistive load R

Case 1 – Short-circuited load ![]() = 0

= 0

The load reflection coefficient in the case is

![]() (5)

(5)

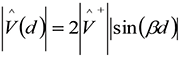

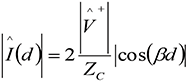

In this case, Equations (4) reduce to [1]:

(6a)

(6a)

(6b)

(6b)

The phase constant β can be expressed in terms of the wavelength λ as

![]() (7)

(7)

and Equations (6) become

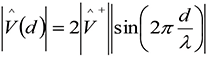

(8a)

(8a)

(8b)

(8b)

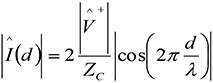

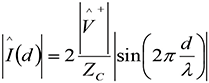

The magnitudes of the voltage and current waves for a short-circuited load are shown in Figure 3.

We observe the following:

- The voltage is zero at the load and at distances from the load which are multiples of a half wavelength.

- The current is maximum at the load and is zero at distances from the load that are odd multiples of a quarter wavelength.

- The corresponding points are separated by one-half wavelength.

Case 2 – Open-circuited load ![]() = ∞

= ∞

The load reflection coefficient in the case is

![]() (9)

(9)

and Equations (8) become [1]:

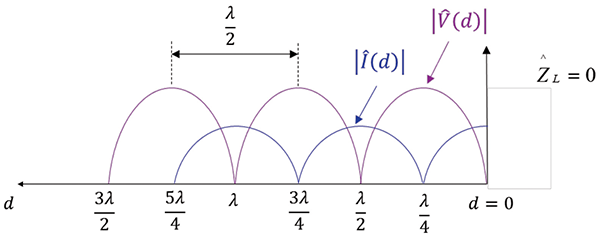

(10a)

(10a)

(10b)

(10b)

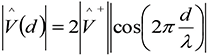

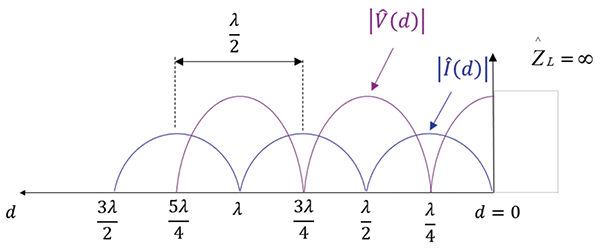

The magnitudes of the voltage and current waves for an open-circuited load are shown in Figure 4.

We observe the following:

- The current is zero at the load and at distances from the load which are multiples of a half wavelength.

- The voltage is maximum at the load and is zero at distances from the load that are odd multiples of a quarter wavelength.

- The corresponding points are separated by one-half wavelength.

In both cases, the voltage and current waves do not travel as the time advances, but stay where they are, only oscillating in time between the stationary zeros. In other words, they do not represent a traveling wave in either direction. The resulting wave is termed a standing wave.

Case 3 – Matched load ![]() = ZC

= ZC

The load reflection coefficient in the case is

![]() (11)

(11)

and Equations (8) become:

(12a)

(12a)

(12b)

(12b)

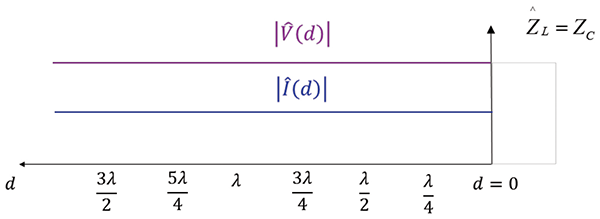

The magnitudes of the voltage and current waves for matched load are shown in Figure 5.

We observe that the voltage and current magnitudes are constant along the line.

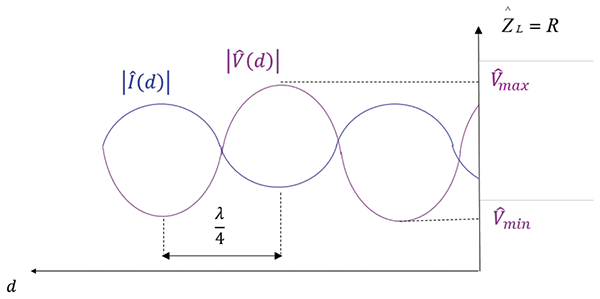

Case 4 – Arbitrary resistive load

The magnitudes of the voltage and current waves for an arbitrary load are given by Equations (8) and are shown in Figure 6.

We observe that the locations of the voltage and current maxima and minima are determined by the actual load impedance, but again, adjacent, corresponding points on each waveform are separated by one-half-wavelength.

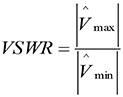

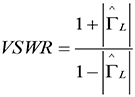

In all cases, except for the matched load, the magnitudes of the voltage and current vary along the line. This variation is quantitatively described by the voltage standing wave ratio (VSWR) defined as

(13)

(13)

VSWR can also be expressed in terms of the magnitude of the load reflection coefficient as

(14)

(14)

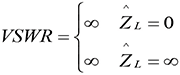

When the load is short-circuited or open-circuited, we have

(15)

(15)

When the load is matched, we have

![]() (16)

(16)

In general,

![]() (17)

(17)

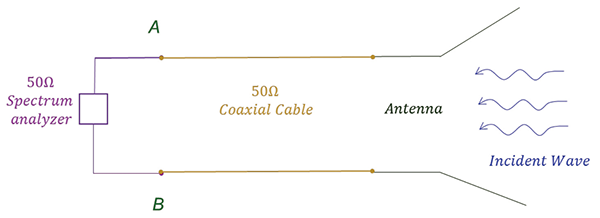

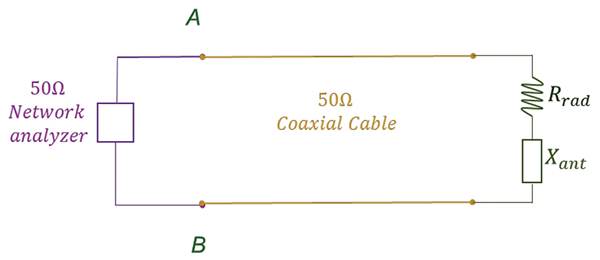

Consider the model of an antenna system in the receiving mode shown in Figure 7.

Spectrum analyzer is matched to the coaxial cable (thus, there are no reflections at the receiver). If the antenna’s radiation resistance were 50 Ω over the measurement frequency range then the voltage induced at the base of the antenna would appear at the spectrum analyzer (assuming no cable loss).

If the antenna’s resistance differed from 50 Ω then some of the power received by the antenna would be reflected back or reradiated and the reading at the spectrum analyzer would be lower.

It is therefore very useful to know the impedance of the antenna over its measurement range. One very good indicator of the antenna impedance is obtained by measuring VSWR of the antenna.

The antenna can be represented by its circuit model consisting of the radiation resistance Rrad and its reactance Xant, as shown in Figure 8.

If, in a given frequency range the antenna’s impedance is purely resistive and equals 50 Ω then the VSWR reading will be 1 (see Case 3 and Eq. (3) in the previous section). The more the impedance of the antenna differs from 50 Ω the higher the VSWR reading.

Application

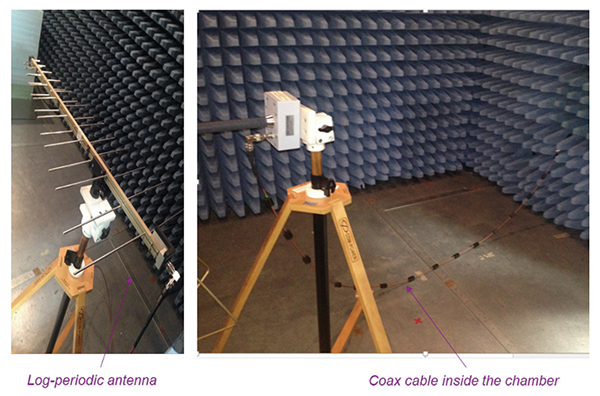

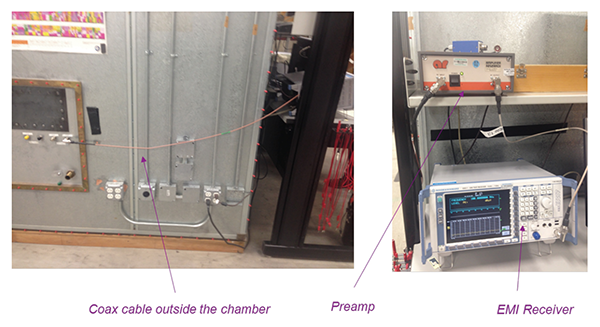

Figures 9 and 10 show the test setup for measuring VSWR of the log-periodic antenna.

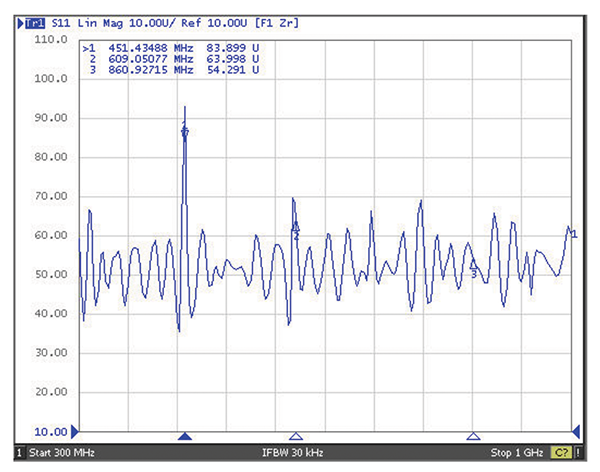

The impedance measurement is shown in Figure 11.

Note that the impedance measurement is very close to the value of 50 Ω in the intended frequency range of this antenna (300 MHz – 1 GHz).

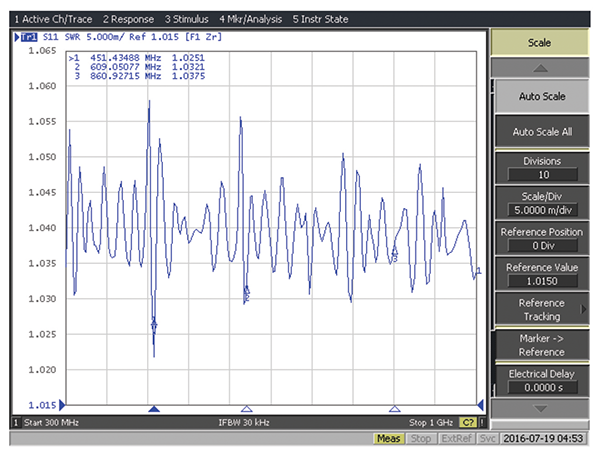

The VSWR measurement for this antenna is shown in Figure 12.

Note that the VSWR is very close to the value of one in the intended frequency range, which is a very desirable antenna behavior for EMC measurements.

References

- Bogdan Adamczyk, Foundations of Electromagnetic Compatibility with Practical Applications, Wiley, 2017.