Although the foundation of a failure analysis is rooted in science, there is also an art to completing one, successfully.

The path from “problem discovery” to “problem solution” has many bumps and twists along the way and this article will hopefully help guide you on your journey. Investigative and analytical skills are a must and need to be implemented effectively in order to reach a useful end. Further, time is typically of utmost importance when performing a failure analysis so knowing how to interpret your results quickly and efficiently will allow you to continue on a forward path. Dead ends will be reached, paths in which the test results offer no apparently useful information; however, one must always bear in mind that a result is truly a result not matter how insignificant it might appear on its own. Being able to eliminate a possible failure mode from the discussion is just as important as identifying the ultimate root cause.

Holistically speaking, an analyst must realize that every failure is unique to the product being investigated; however, experience in performing failure analyses is critical as failure symptoms are very common and your knowledge about them is priceless when trying to diagnose a “new” failure. Additionally, the gathering of background/historical information about the specimen being investigated is crucial in determining which steps should be taken along your failure analysis path. Knowing the types of questions to ask and what information you should try to obtain is a useful tool.

Within this article we will discuss how to “attack” printed circuit board (PCB)/printed circuit assembly (PCA) specimens when performing a failure analysis. Specific test methodologies will be discussed with descriptions of the associated test equipment and what an analyst may expect to glean from the results. With the analysis portion complete, we’ll then discuss report writing and what to do the next time a failed specimen ends up in your hands for analysis!

Getting Background Information

From the “source” of the failure – the person, person(s), department, division, company, etc., that has given you the task of analyzing the failed specimen, you should first obtain the exact goals that are expected from the analysis you are about to perform. Specifically, you should determine if the “source” has specific questions that need to be answered in order for them to satisfy the original query. Be sure to document these goals/questions and refer back to them often as you move forward in your failure analysis.

Additionally, you should try and secure as many of the following items as possible:

- Representative failed specimens

- Representative non-failed specimens

- Representative components/materials that comprise the failed specimens

- Representative process chemicals that may have been used in the construction, cleaning, handling etc. of the failed specimens, and most importantly….

You as the analyst need to gather as much information as possible concerning the manufacturing of the product, the exact nature of the failure, the way in which the failure was detected, and the environment in which the failure occurred/was detected.

For the analysis you are about to perform, time will almost always be in short supply.

Failures typically result in some kind of “down” condition for your “source” and they will be anxious to receive information as soon as you have it. That being said, you must make quick and sound decisions along your path. Do not rush; simply use the information you have at that time to make a scientific decision about where to go next. Sometimes an allotment of failed and non-failed specimens will allow you some leeway in making these decisions as incorrect decisions won’t be costly; however, in most instances, failed specimens will be at a premium, along with representative non-failed specimens of the same date code, lot number, etc., and you will have to make sure you “conserve” the samples you have and use them to gather as much information as possible. There will even be instances where only a single test can be performed due to its destructive nature. In a situation such as this, you must simply choose the test that will get you the most information and then try and supplement the results in other ways.

With the groundwork set, off we go…

The Initial Examination

Before doing absolutely anything with the failed specimens, find a clean and clutter-free location in which you can “spread out” all of the supplied specimens and get yourself organized before beginning. At this point, be sure to inspect each test specimen for its proper identification/serialization and record this information for future use when preparing samples for test or for when writing your test report.

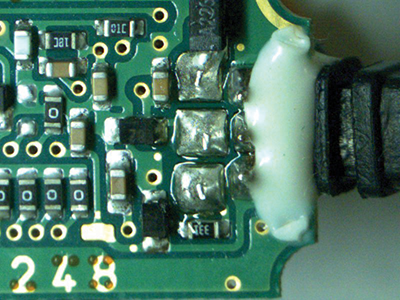

When ready to begin, use various light sources (natural, fiber optic, IR, etc.), magnifications (via a standard bench microscope or stereomicroscope), and visual enhancement techniques (backlighting, diffused lighting, mirrors, etc.) to perform a detailed visual examination of each and every specimen you have received. Obviously you should concentrate on the specific failure area, as identified by your “source”, but be sure to look around at other similar areas on the same or different specimens depending on what you have received for review. Information in respect to both failed and non-failed areas will be useful later on, and of course, be sure to record and photograph your observations – remember that you will need overview and close-up images to “show” the situation to your “source” later on when compiling the test report.

To get you started, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer with your Initial Visual Examination:

- Is there visual confirmation of the failure issue?

- Are there other similar or adjacent areas affected by the failure issue?

- Do all or some of the specimens exhibit the same failure condition?

- How many areas are or how much of the area is affected by the failure?

- In layman’s terms, what does the failure look like (be simple – color, shape, size, etc.)?

- Is there an industry wide “name” for the failure issue/condition that you are observing?

- Do you see anomalies other than those mentioned/described by your “source”?

With the completion of your initial visual examination, the next step on your failure analysis journey must be determined. Bearing in mind your identified failure issue, you must decide whether non-destructive or destructive testing is where you should be heading. In almost every case, you as the analyst should exhaust any and all non-destructive test techniques at your disposal before turning to destructive test techniques. Why? The answer should be obvious; especially if you’ve yet to visually confirm the failure issue…performing a destructive test too early in the process could damage the true location of the failure and ultimately inhibit your ability to solve the problem at hand…thus, utilize all non-destructive test techniques!

Non-Destructive Test Techniques

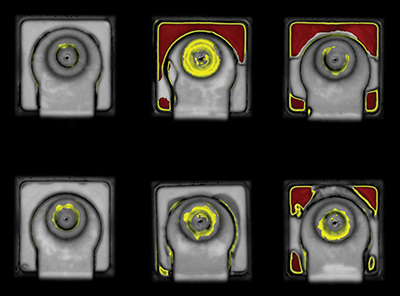

In addition to the traditional visual examination, various other “visual” techniques can be used to help “see” your failed specimen in a different way. Two (2) common techniques are: X-Ray Examination and Scanning Acoustic Microscopy (SAM). Each of these techniques, in their own way, provide a visual means of seeing things associated with your specimen that you couldn’t see with the naked eye or even a standard stereomicroscope.

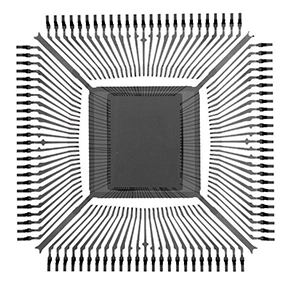

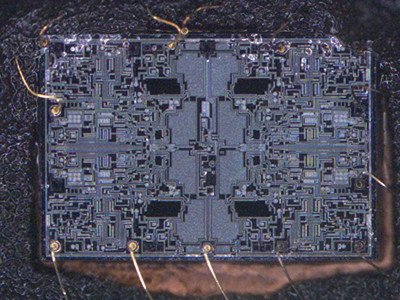

The use of x-ray allows you to see inside the “black box”, internal structures that are not visible under normal conditions are now visible. Missing/broken wire bonds, misaligned components, and evidence of counterfeiting are some of the characteristics that can be seen using x-ray, in both 2D and 3D aspects. The 2D technique does have inherent limitations however, as the image you see of your specimen is a “thru” shot in which anything in the path of the beam is visualized. With this, some anomalies might not be seen, such as a BGA solder joint separation at the board interface, while some areas of the failed specimen might not even be able to be visualized if structures on the opposite site of the board are in the sight line of the region of interest. For more detailed inspection, the 3D (or CT scanning) technique can be used, for which interactive modeling can be acquired.

As a complement to examination via x-ray, SAM can be used to inspect for anomalies not traditionally seen via x-ray. Of specific interest, SAM is typically used to look for internal anomalies such as delamination, voiding, and or cracking within a component structure. The scattering of the acoustic signal when air is “struck” at one of these anomalies causes a response in the imaging that allows you to see where and to what extent the internal problem is present. Area or volume calculations can also be performed to better quantify the anomaly.

delaminated areas shown in yellow/red

For these additional “visual” examination techniques, the same simple questions that were mentioned above may give “better” answers this time around.

Moving from visual examination techniques to something a bit more quantitative, while assuming that the failure is electrical in nature, an electrical examination should be performed as a next step in the process. This evaluation is another extension of trying to qualify the nature of the failure, as an open circuit will be approached much differently than a shorted circuit, not to mention the difference between a high-resistance and a low-resistance short circuit.

For this examination, you should focus on the area of interest as specified by the “source” and obtain electrical characterization information on the failed specimen as well as on the non-failed specimens. In doing this comparison, attempts should also be made to isolate the anomalous conditions if at all possible. And, as always, record everything that you’ve done regardless of whether you currently feel that the result is useless. As described in the Introduction section above, one must always bear in mind that a result is truly a result no matter how insignificant it might appear at the time.

While performing the electrical examination, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Is there an electrical confirmation of the failure issue?

- Based on your previous experiences, what type of issue would these electrical characteristics cause/create?

- Is it possible that other areas of the specimen are affected?

- How many areas are affected by the failure issue?

- Does the failure condition have a technical name?

- Do you see anomalies other than those mentioned by the “source”?

With the main non-destructive test techniques now exhausted and with your failure issue (hopefully) now located, identified, and characterized to the best of your “non-destructive” abilities, it’s time to move on to destructive techniques. Listed in the paragraphs below are various test techniques that inherently cause “damage” to your test specimen. That being said, you must make wise decisions about the sequence in which the testing should be performed in order to maximize the amount of information that can be gleaned from your failed specimen while also minimizing the amount of peripheral damage to the specimen. After all, if you hit a “dead end” with your initially chosen analysis path, you’ll need to re-group and having leftover specimen to test will be critical.

Destructive Test Techniques

With specific information about the failure issue in your back pocket and having had a primary view of the anomaly at hand, decisions must now be made in regard to the specimen’s disposition and exactly in what direction your analysis should be headed. For most PCB/PCA based failure analyses, the path you choose is dependent on “where” the failure issue is occurring. By that, we mean what step in the process of the PCA’s construction does the failure issue appear to be manifesting itself. From the evaluations performed above, you should be able to categorize your failure analysis as one of the following – board level or assembly level.

Based on this classification, your first path decision can now be made. The “level” you’ve selected will point you towards “properties” that should be investigated. Table 1 is a list of destructive test techniques and the associated “properties” that can be found as a result – note, the testing listed below is not meant to be an all-inclusive list but simply a punch list of tests that are typically performed on PCB/PCA type specimens. Choose test techniques that will give results that are pertinent for the failure issue that you are investigating, but don’t forget about all pieces of the puzzle that you are trying to solve. An analyst should not put on blinders when heading towards a solution and you should be aware that sometimes the most influential results are found when performing a test in a specific way. That being said – be creative! The “art” of failure analysis is that it is an ever evolving idea and a little creativity in selecting your test methodology never hurts.

The following paragraphs provide insight and guidance on each destructive test technique listed in Table 1. The purpose of the specific testing is given along with some questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about.

Decapsulation

This specific test is more of a sample preparation technique and would be used if the failure issue under investigation is related to the assembly level, or more specifically, the component level. Decapsulation allows for the removal of component encapsulant material such that an internal die structure can be primarily viewed using normal visual techniques or SEM. This inspection can be used as a check of the internal bond wire structures as well as before a detailed examination of the die’s surface.

When inspecting the internal structures of a decapsulated component, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Are bond wires present within the component and are they structurally sound?

- Does the internal die appear to be intact?

- Is there any evidence of electrostatic discharge (ESD) damage?

- Could the component and/or the die be a counterfeit?

- How does the failed component compare to a non-failed (exemplar) component?

|

Destructive Test Technique |

“Property” |

|

Decapsulation |

Die Inspection |

|

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) |

Degree of Cure (ΔTg), Glass Transition Temperature (Tg), Melting Point (MP) |

|

Dye-n-Pry Analysis |

Solder Joint Fracture, Solder Joint Strength |

|

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy |

Contamination, organic-based |

|

Ion Chromatography (IC) |

Contamination, ionic-based |

|

Microsection Analysis |

Board Integrity |

|

Scanning Electron Microscopy / Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS) |

Contamination, inorganic-based |

|

Solderability Analysis |

Solderability |

|

Thermal Stress Analysis |

Board Integrity |

|

Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA) |

Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE), Time to Delamination |

Table 1: The role of various destructive test techniques

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

This specific test would typically be conducted for failure issues related to either the board level or the assembly level, given the fact that assembly level failure issues can at times be the result of poor board level construction. Gaining information about a board’s cure status can be extremely useful in trying to determine exactly what is occurring. Specifically, this test method is of great interest if the lack of cure of the board could be contributing to the mode of failure, such that it causes excess expansion of the board during the soldering process. Additionally, if Pb-containing versus Pb-free processing is involved, basic material information about the board’s glass transition temperature (Tg) could be useful. Further, if possible, you should attempt to compare the failed sample board’s properties to that of a non-failed board to determine whether or not the specific property of interest is truly an issue.

While performing this DSC Analysis, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- What is the glass transition temperature of the board sample?

- What was the degree of cure of the board sample?

- Is it possible/probable that the degree of cure could be causing the failure issue?

- Given the degree of cure found, what types of problems could this cause/create?

- Do all of the samples, failed and non-failed, exhibit the same condition?

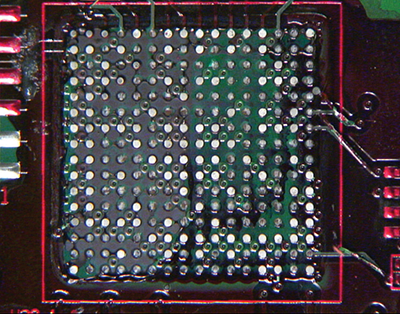

Dye-n-Pry

This specific test is typically used for failure issues related to BGA components, although it can be used with some modification for other component types, and would thus be investigated in relation to an assembly level failure. Dye-n-Pry analysis involves the removal of a BGA component in such a way that each individual solder joint can be evaluated for the possibility of an open circuit. Dye penetrant is flowed beneath the component such that the fluid is allowed to “submerge” each individual solder joint ball. Then, once the dye is cured, the component is removed from the board with each of the solder joints beneath each primarily observed. Ultimately, this post-component removal inspection can be used to determine if any open solder joints are indeed present. For solder joints that have some type of failure issue, the dye material will be visible “within” the joint.

When inspecting the Dye-n-Pry test location after component removal, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Are any open, fully or partially, solder joints present?

- For each open solder joint, at which interface – component/solder versus solder/board – has the separation occurred?

- Is there any evidence of head-in-pillow defect –

a defect in which the solder joint does not completely reflow resulting in the solder paste on the board and the solder ball not “combining”? - Is there any evidence of pad cratering – a defect in which the board material has cracked beneath a given surface mount pad?

- Are there any apparent solder wetting issues?

Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

This specific test would typically be conducted for failure issues related to the assembly level; specifically, when it is believed that an organic contaminant might be causing visible corrosion or might be contributing to some type of high resistance short. To help determine the exact failure issue, comparing failed and non-failed locations is useful to assist in identifying what organic materials are supposed to be present in comparison to those that are not supposed to be present.

When reviewing the FTIR test results, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Was an organic contamination/material detected by FTIR?

- Specifically, what organic material was detected?

- Is it possible that this organic contamination/material could be causing the failure issue?

- What type of issue would an organic contamination such as this cause/create?

- Is this an isolated issue or are there other areas affected?

- Do all of the supplied specimens exhibit the same condition?

Ion Chromatography (IC)

This specific testing could be conducted for failure issues related to either the board or the assembly level. An analysis via IC would be performed if it is believed that ionic material on the specimen’s surface could be leading to a high resistance short or some sort of electrical “leakage”. The testing itself can be performed on a board basis through full extraction or on a localized basis through spot checks at various areas on the specimen’s surface. If the “source” has known ionic cleanliness requirements, this information might be helpful in determining what is occurring in respect to the failure mode at hand. Pass/fail criteria for a test such as IC is not always a definitive way to determine if the specimen is truly “clean”. A localized concentration of ionic residues would be problematic regardless of the specimens’ overall cleanliness level.

When reviewing the IC test results, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- What types of ionic contamination were detected by IC?

- Is it possible that the ionic levels detected could be causing the failure issue?

- What type of issue would the ionic contamination levels detected cause/create?

- Do some of the individual ionic levels suggest a potential source for the “contaminant”?

- Do both failed and non-failed specimens exhibit the same or similar ionic levels?

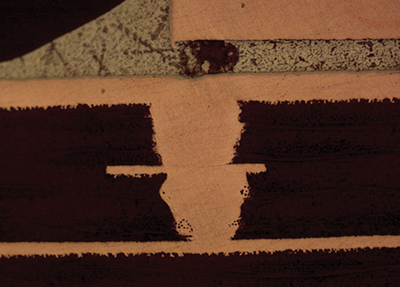

Microsection Analysis

This evaluation would typically be conducted for failure issues related to the board level and/or the assembly level for examination of internal board anomalies and/or solder joint related anomalies. For the analysis, the specimens of interest are diced and mounted in an epoxy resin to allow for cross-sectional examination via metallurgical scope of the board/solder joints in either the vertical or horizontal plane, depending on the situation at hand. Evaluation can be performed in a generic sense, simply commenting on what is “seen” or “not seen”, or to an industry standard, such as IPC-A-600 and/or IPC-A-610. Once again, it is best to compare failed regions to non-failed regions for comparison purposes while taking many photographs to tell the story of what is occurring – always keep in mind the report that you will need to write upon completion of your analysis!

When evaluating your prepared microsection samples, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Are there any internal board issues that could be causing the failure issue?

- Are there other areas of the specimen that are showing the same anomaly?

- Do all of the supplied specimens, both failed and non-failed, exhibit the same condition?

- In layman’s terms, what does the failure look like (be simple – color, shape, size, etc.)?

- Is there an industry wide “name” for the failure issue/condition that you are observing?

- Do you see anomalies other than those mentioned by the “source”?

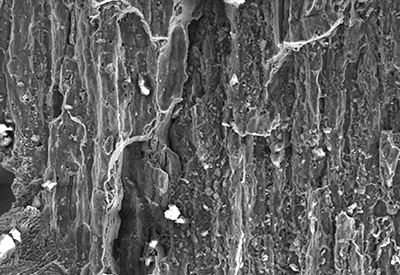

Scanning Electron Microscopy/Energy Dispersive X-Ray Spectroscopy (SEM/EDS)

This testing is typically performed for failure issues related to the assembly level but can also be used to help further evaluate possible board level anomalies. SEM/EDS provides both visual and elemental information about the selected area(s) of interest. SEM provides an additional way to visually inspect a sample. The magnifications reached by SEM will be much higher than that that can be obtained by stereomicroscope or metallurgical scope – and don’t forget to take photographs – lots of them! At the same time, EDS provides elemental information about an observed contaminant, a corrosion product, or about elemental distribution (homogeneity vs non-homogeneity) in the area of interest. Typically, these types of materials could be causing a high resistance short and thus need to be evaluated, elementally, in order to determine their composition and then possibly their origin. Comparing failed and non-failed (or contaminated and non-contaminated) locations is best for determining what elements should be present and which ones should not be present.

When reviewing the SEM/EDS test results, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- Via SEM, did inspection at a higher magnification provide any additional detail to that which was already observed using a stereomicroscope and/or a metallurgical scope?

- Via EDS, did the identification and quantification of the elemental species present provide any significant information about the observed contaminant/corrosion material?

- Are there other areas of the specimen that are showing the same anomaly?

- Do all of the supplied specimens exhibit the same condition, both failed and non-failed?

- Do you see anomalies other than those mentioned by the “source”?

Solderability Analysis

This testing would typically be conducted for failure issues related to either the board level or the assembly level. Confirming whether or not a board can “pass” IPC-J-STD solderability testing is a crucial piece of information when trying to evaluate the cause of a failure, specifically a solder joint failure. When possible, you should attempt to perform this analysis on as many representative samples as possible bearing in mind that surface mount pads may not solder the same as a plated through hole.

When performing the Solderability test, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- How “well” did the specimen solder?

- Did the specimen meet its IPC-J-STD solderability requirement?

- Could the solderability test result explain or be related to the failure issue?

- What type of issue would a solderability issue such as this cause/create?

- Do all of the supplied specimens exhibit the same condition?

Thermal Stress Analysis

This specific type of testing could be conducted for failure issues related to either the board level or the assembly level. Confirming whether or not a board can “withstand” repetitive solder reflow cycles is worth a look. After performing the test, microsection specimens are typically prepared and then evaluated to look for anomalies that might be similar to that which has been observed on the failed specimen.

When evaluating the specimens after the Thermal Stress Analysis, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- After completion of the Thermal Stress Analysis, were any visual anomalies detected?

- Were the anomalies found similar to the failure issue observed?

- Is there an industry wide “name” for the failure issue/condition that you are observing?

- Do all of the supplied specimens exhibit the same condition?

Thermomechanical Analysis (TMA)

This specific test would typically be conducted for failure issues related to either the board level or the assembly level. Obtaining information about a board’s expansion properties is a useful piece of information when trying to diagnose the failure issue at hand. Using TMA, thermal expansion properties can be evaluated both in terms of the board’s coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) and through observation of the board’s behavior when it is held at elevated temperature for an extended period of time, like during solder reflow. For example, if a board delaminates during the reflow process, it would result in a solder joint issue that is being experienced on the assembly level with the cause actually being due to a board level problem.

While performing this TMA Analysis, here is a list of some simple questions that you might try to answer or obtain information about:

- What are the pre- and post- glass transition temperature (Tg) CTE’s for the board sample?

- What is the “overall” thermal expansion (TE) for the board sample?

- Are the CTE and TE values found “typical” given the board’s construction?

- Can the board sample survive Time-to-Delamination testing?

- Is it possible/probable that the board’s performance at elevated temperature is causing the failure issue?

- What types of problems could the thermal expansion properties cause/create?

- Do all of the specimens, failed and non-failed, exhibit the same properties?

Ending Your Analysis

Knowing when to stop your analysis is almost as difficult as knowing where to start your analysis. The big difference on this end of the path is that you will know when enough is enough when you can answer these questions …

- Do I have enough information to explain to my “source” what has happened to the failed sample?

- Do I have enough information to explain to my “source” why this has happened to the failed sample?

- Do I have enough information to answer all of the questions that my “source” had?

- Do I have enough information to explain to my “source” how they can avoid this issue in the future?

The common theme in these questions is “information”. Each and every failure analysis should focus on information – the more the better. This starts from the very beginning, as mentioned above, when you as the analyst must gather all of the appropriate background information so that you can get your failure analysis headed in the correct direction right from the start. From there, you make decisions on how to progress based on the information that you have gathered from each test you’ve selected along your path. The various sets of questions listed above for each of the test methodologies described are given to help you gather this information. You must then use the path to gather more and more information until enough is gathered for you to easily and successfully write a test report that your “source” can understand and use to understand/solve the failure issue at hand.

Writing the Report

Most failure analysis reports are quite detailed and become quite lengthy due to the many pages of photographs and instrument scans. These items are interesting to look at and do indeed tell a part of the story; however, for most people reading the report, the “results” given in these items will most likely not be understood in the context of simple presentation. That being said, the verbiage that you supply as the analyst, and now as the author, is the glue that will bring all of your hard work together. You truly will be an author at this point as you need to tell the “story” of your analysis. You need to establish the failure issue at hand and then explain how you went about attacking that problem. The report has to have structure and should flow from section to section. The following is a description of a typical failure analysis report layout:

Section I – The Abstract: When writing a failure analysis report it is always a good idea to include a statement of work (SOW) to get things started. This SOW can likely be taken directly from your “source’s” initial contact with you. The SOW will state exactly what the source needs you to determine; for example, “John Smith is experiencing an intermittent open at BGA component location U1 on PCA S/N 12345678.” This type of statement gets the ball rolling in the report and allows you to then follow up with the background information that you have gathered. By including the background information obtained, as discussed earlier in this article, you can paint a picture of how the failure issue at hand has come about. This section will give the history of the specimen as well as any troubleshooting that may have been done on the specimen prior to you coming into possession of it. In the end, the Abstract should be a summary of the information that you were given or obtained prior to the commencement of any testing, non-destructive or destructive.

Section II – The Body: After clearly establishing the failure issue at hand and after presenting the information surrounding the failure itself, it is now time to jump right into the testing that you’ve performed. Section II will make up most of your test report and should include sub-sections for each of the test methodologies that you implemented in your analysis no matter the result! Within these individual sections you should describe the samples selected for analysis, the methodology performed, and the results. These results should include any “visual” observations or “numerical” values that you’ve come upon that help show the work that you’ve performed. At the same time, unless you feel compelled, there is no real need at this level of the report to describe how a particular single result is related to the failure issue at hand, but you can make some commentary if you’d like – it is after all your report. Ultimately, the root cause of the failure issue will likely be drawn from the results of multiple analyses performed and that is why it is ok to simply state results in this section of the report and nothing more – in essence, conclusions are for the conclusions section! That being said, it is entirely possible that no single test result will mean anything standing alone and only when all of the results are put together will a true root cause be found.

Section III – Appendix: With all of your hard

work described in words, photographs, tables, and figures in Section II of the report, don’t forget to include all of the “other” information that you’ve gathered. Spectra, scans, and the like should all be included in your test report as support for the information that you’ve provided in the individual test sections. Most of this information might never be looked at by your audience but it most definitely needs to be there in some form. Provide a list of what you are including and then simply attach everything for reference as needed.

With these three report sections written, I, II, and III; the last section to write ends up becoming the first one in the organization and the most important one to boot! We’ll call it Section “0”…

Section “0” – The Analytical Summary: Given that your audience will include your “source” and likely your “source’s” manager or director, you might as well get to the good stuff right away in your report as “some people” aren’t going to want to read all the way to the end! I have found it to be very useful to put the Analytical Summary right up at the front of the report before anything else. This summary should be no more than one to two pages and should highlight the SOW, the Abstract information, the results that you’ve found throughout your testing and then, most importantly, your conclusions and recommendations. This latter part is clearly and rightfully the most difficult part of your job on this failure analysis. As the analyst, you are responsible for tying everything together and interpreting the results in a way that everyone involved can understand. It is, at times, not an easy job, but given experience and knowledge, the path you’ve taken will lead you directly to the “answer”. For your conclusions and recommendations in this section, here is some helpful advice:

- Try and limit your conclusions for the root cause of the failure issue to one or two possible causes

- Try and recommend any possible corrective actions, preventative actions, or repairs that might allow your “source” to avoid this failure issue/mode in the future

- Be sure to specifically answer as many of the questions in the “source’s” SOW as possible

- Depending on the failure issue/mode, try and compile supporting literature that might be useful to your “source”

- Be as definitive as possible in your statements about the testing you performed and your findings; try to avoid the words – possibly, probably, maybe, etc.

Lastly, when writing, try to keep in mind the “audience” to which you are writing. It is very likely that your report will be read/reviewed by people of various technical backgrounds. It is okay to assume some level of technical expertise by your “readers”, but at the same time you have to be cognizant that they also might not be as educated as you on the topic/findings.

Summary

In this article, a “road map” for a successful failure analysis has been laid out. As you can see, there are many twists and turns that need to be managed and the amount of information and types of specimens that you are given by your “source” will have a profound effect on what exactly it is that you are trying to accomplish as well as how well you might be able to accomplish it. Sometimes a failure mode won’t be found, sometimes the evidence of the failure won’t be found in a lab setting, and sometimes all of the evidence of the failure is gone at the time of the analysis, even in situations such as these, useful information can still be found if searched for in the appropriate manner and conclusions can likely be drawn based off of the results obtained from “similar” specimens. Like a police investigation, PCB/PCA failure analysis can be “done by the book” and when that happens, good things usually result.

Keith Sellers, the Operations Manager at NTS-Baltimore’s facility in Hunt Valley, MD, has been with NTS (formerly Trace Laboratories) since 1999 and holds a bachelor’s degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Delaware. NTS-Baltimore specializes in materials-based testing, with a common focus in the areas of contamination and root cause failure analysis. Additionally, the facility does a tremendous amount of work in various PCB/PCA related fields such as environmental stress screening, Pb-free alternatives, tin whiskers, ionic cleanliness, counterfeit components, and many other related reliability focused fields of testing. He can be reached at Keith.Sellers@nts.com.

Keith Sellers, the Operations Manager at NTS-Baltimore’s facility in Hunt Valley, MD, has been with NTS (formerly Trace Laboratories) since 1999 and holds a bachelor’s degree in Chemical Engineering from the University of Delaware. NTS-Baltimore specializes in materials-based testing, with a common focus in the areas of contamination and root cause failure analysis. Additionally, the facility does a tremendous amount of work in various PCB/PCA related fields such as environmental stress screening, Pb-free alternatives, tin whiskers, ionic cleanliness, counterfeit components, and many other related reliability focused fields of testing. He can be reached at Keith.Sellers@nts.com.